IT TAKES A WHOLE VILLAGE TO RAISE A CHILD

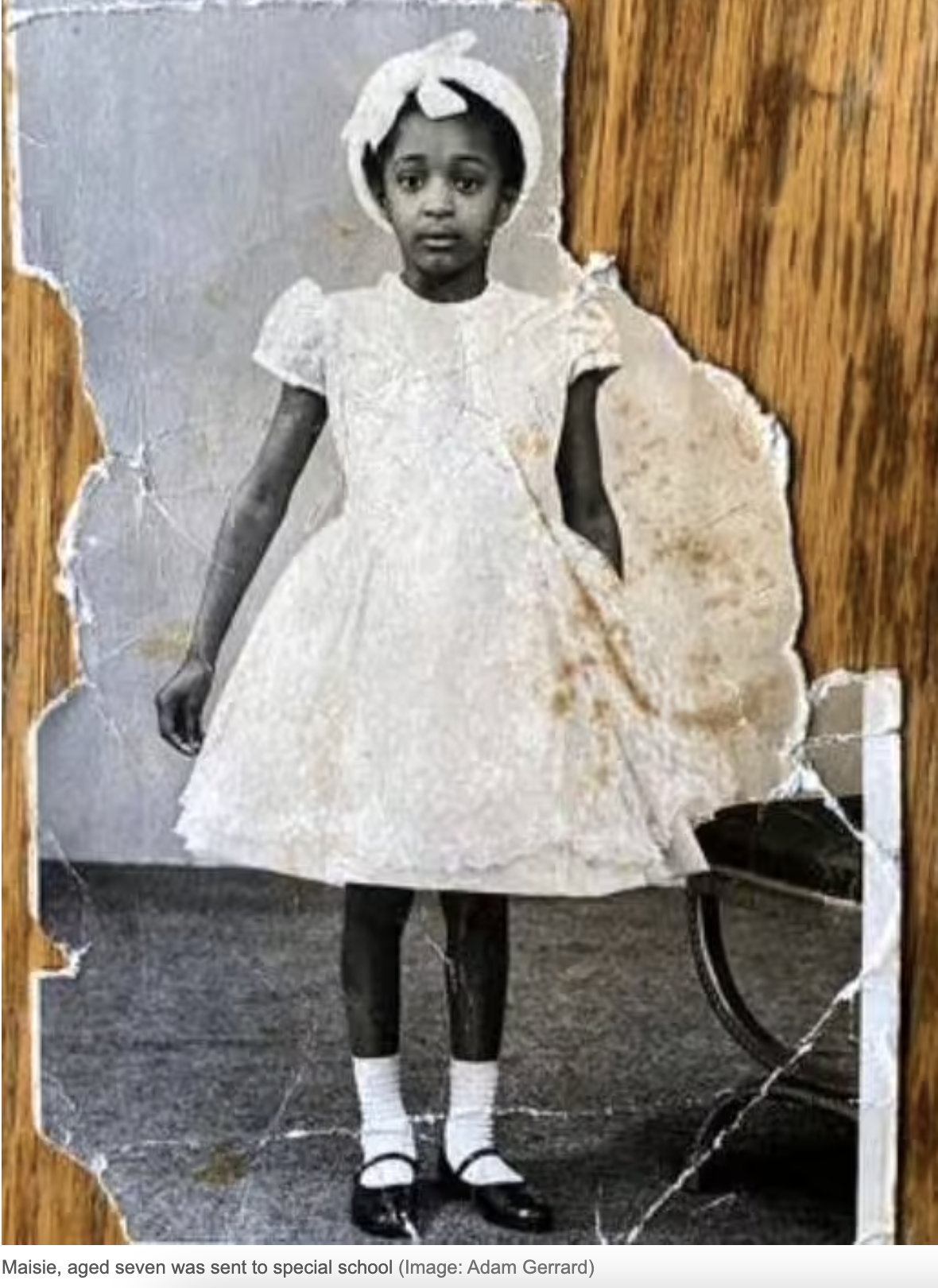

Writer Maisie Barratt shares her story of being labelled ‘educationally sub-normal’, the systemic racism within the UK’s education system and the life-long impacts this has had on her and her family.

StoriesMaisie wrote and delivered this highly personal and affecting talk at Cambridge Central Library in 2024, an event supported by the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Public Programme. We are grateful to have her permission to re-share her story on Future Legacies.

Although I was born in Birmingham, my story truly began in Leeds when my parents bought a six-bedroom Victorian house when I was 3 years old. By the time my father died in 1973, I was 14 years old, and I could not read or write, and I had little social skills. When I was 6 years old, I underwent a superficial assessment, and the Education Authority placed me in an ESN [‘educationally sub-normal’] school. Once there, I received no education because my teachers thought I was inherently backward because of my race, and incapable of learning.

I was born at a time in England when it was common to hear the saying that goes, ‘children are seen and not heard’. It was a time when I would often hear the Biblical phrase, ‘do not spare the rod and spoil the child’. Which (in my opinion) means, ‘do not spare the rod and spoil the slave,’ (just don’t kill them). Exodus 21:20-21.

My father called the rod, the ‘cowcod’ which was a very thick rubber thing he used to take from his workplace to beat me with. It was a time when most West Indian homes were almost identical to that of the slave community, when you would often hear the slave master (my father), beating his slaves – my mother and me. We had to obey him or else. When the six-week holidays ended, my parents would say to me ‘You Free Paper soon burn,’ meaning school would start soon and the learning would begin again, which, like home it was a violent place to be. The Free Paper was an enslaved person’s pass when leaving the plantation.

Until 1986, schools in Britain and Europe resembled slave communities in the Americas, where teachers could physically punish children, if they failed to learn or obey.

After the abolition of slavery, the ex-enslaved Africans anxiously waited for the White Paper, also called Free Paper, to prove that they were now free at last, or they would be punished. The teacher would still hit them with a ruler and make them feel inferior, which in turn caused behavioural problems – another excuse to put a Black child in an ESN school. Fortunate for me, I did not get beaten at school only at home. You will see why later. Despite my parents’ love for me, particularly my mother, I felt unsure of their love due to this Christian slave mindset when children could be beaten like a slave. Growing up, I faced silence at home because I was just a child, I must be seen and not heard, or I will get whipped. The same silence awaited me at school, where my Blackness made me invisible.

I was born at a time when racism was overt in England. It was violent and in your face. The arrival of British West Indian subjects carrying their suitcases and searching for a room, but turned away because of the colour of their skin, is a historical scene that has become a cliché that must never fade away in British history. They turned away the Irish too, but eventually they could slowly assimilate into whiteness because they are white, whereas Black people continued to be racially marginalised. Landlords did not want families with dogs. West Indians did not have dogs, but they had children.

Once they secured a job and a room, the next crucial objective was to find a school for their children. This proved to be exceedingly difficult, especially when we started to migrate to Britain by the thousands. Now, there were too many children that had to go to school. From the first World War, but more so during the Second War until 1964, witnessed inter-marriages between Black American and West Indian soldiers with white women, which caused the rise of the birth of brown babies, who had to go to school.

Powell declared that Black people were inherently less intelligent than whites, and therefore Black children should be taught separately.

In 1964, 300,000 West Indians were living in Britain, and they were still coming until the early 1970s and beyond. And thus, West Indians were quickly shaping and changing the colour of Britain and both the Government and English people were terribly angry. Over time, this caused the birth of the famous Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech when he was talking about the growing Black presence in Britain in the House of Commons. In the speech he talks about the fear of one English man.

He says, ‘A week or two ago I fell into conversation with a constituent, a middle-aged, quite ordinary working man employed in one of our nationalised industries. After a sentence or two about the weather, he suddenly said: ‘If I had the money to go, I wouldn’t stay in this country. I have three children, all of them been through grammar school and two of them married now, with family. I shan’t be satisfied till I have seen them all settled overseas. In this country, in 15 or 20 years’ time, the Blackman will have the whip hand over the white man.’

Unlike today’s West Indians, who come to Britain, the Windrush subjects did not come to stay, which is the greatest irony here. The plan for most West Indians was to return home within 10 years. So, they had bank accounts here and, in the Caribbean, and they were sending money home every month. West Indians bought houses only because they could not get a decent place to live. What happens when you have a mortgage to pay, and you start having children? It is not that easy to get up and go.

Just like the gentleman in Powell’s speech, West Indians relocated to England with the intention of improving their lives and ensuring a good education for their children, but their hopes were impeded right from the start. Powell declared that Black people were inherently less intelligent than whites and therefore Black children should be taught separately.

Teachers gave West Indian children IQ tests with the knowledge that their accent and culture would cause them to fail.

Therefore, the British Education System convinced West Indian parents that their children required special educational needs, but they were unaware that these schools would make their children educationally subnormal. For this reason, they would not thrive in society after leaving these schools and would just survive as illiterate people, doing the menial work most of their parents came to do. The only problem is, not everyone is meant to become a cleaner or work in a factory all their lives. When I left school, I could not even fill out a form to apply for a cleaning job and neither did I want to be a cleaner. I wanted to be an actor.

So, why did Black children go to ESN schools? The reluctance to rent homes to West Indian families with children extended beyond landlords; even middle-class white teachers and working-class parents did not want Black children in their schools, because they saw them as an inferior race. According to the documentary, ‘Subnormal: A British Scandal’, by Lyttanya Shannon and executive produced by Steve McQueen, teachers gave West Indian children IQ tests with the knowledge that their accent and culture would cause them to fail. Upon failing these tests, was evidence that Black children were indeed inferior and innately less intelligent than white children and would do better in an ESN school. There was no curriculum or daily structure, and they left the children to play, draw, and read books by looking at the pictures, like I often did. I was still tracing letters when I was 12 years old. ESN schools also accommodated poor white working-class children, who often experienced substantial mental health, learning, and physical challenges, occasionally arriving at school unclean, although not all of them. I remember my teacher asking me to take them to the toilet and wash them down.

Bernard Coard’s essay ‘High Quality Education for All’ emphasises the negative consequences of failing one generation of children in future generations. ‘We human beings ‘inherit’ not only through our genes, but often also from our social circumstances’, which was the ultimate plan, anyway. Even in mainstream schools, Black children were in the lowest classes and were encouraged to leave when they had reached school-leaving age, even though their parents wished them to continue their education. Coard identifies two additional factors, alongside racism, that played a role in shaping the lives of Black children. Teachers and headteachers alike were often patronising. According to Coard, he overheard a teacher saying, ‘I really like that coloured child. He is quite bright fora coloured child!’ I was told I had a nice smile, straight features for a Black child, and that I would make a good nurse after ordering me to take a child to the toilet to wash them, but they did not tell me I had to read and write first to become a nurse.

Having a low expectation of a child can hinder their performance.

Low expectations of Black children, and any child in general, are pointed out as the third factor by Coard. He brings our attention to an experiment carried out in America where ‘…experts in education conducted IQ tests on the children in a particular school in San Francisco. They did not tell the teachers the true results of the tests. Instead, they picked at random twenty names of children from the school and told the teachers that these were the bright children, even though they were not. At the end of the year, the children were tested again, and the teachers were asked many questions about them. The twenty who the teachers thought were the brightest did far better than the rest (though initially they were not the best). They got higher scores than the other children in the IQ test’ (and they were happier).’

Coard goes on to further demonstrate how having a low expectation of a child can hinder their performance. Epileptic children in London, who experience prejudice like Black children (though not as severe), underwent an IQ test. The teachers, unaware of the test results, were asked to assess the children’s intelligence by indicating if they were average, above average, or well above average based on their knowledge of each child. Their teachers, not knowing the result of the test, were then asked to give their assessment. Based on their prejudiced beliefs, they seriously underestimated the child’s true ability says Coard and were wrongly assessed. You can just imagine the outcome if they were black and Epileptic.

My teachers chose me to play Angel Gabriel when I was six years old because they knew I had the talent.

Black children were set up to fail by the Education Authority, causing some West Indian parents to send their kids to the Caribbean for a better education. Jacqueline McKenzie (a lawyer at Leigh Day Solicitors), her parents serve as a prime example of this. As a result of sending her to Grenada to go to school, Jacqui (who is my solicitor) is now a famous, celebrated British human rights lawyer with expertise in migration, asylum, and refugee law. As for my parents, at first, they trusted the system like most West Indians. By the time my mother realised the education authority’s racist plan, due to the publication of Bernard Coard book, ‘How the West Indian Child Is Made Educationally Sub-normal in the British School System: The Scandal of the Black Child in Schools in Britain’, it was already too late for me.

During the 50s and 60s, teachers lacked understanding of dyslexia, but middle-class qualified teachers could have recognised certain symptoms of dyslexia in me. I was a slow learner, so I did not stand a chance to avoid not going to an ESN school. They did not even give me an IQ test because they knew that all they had to do, was to give me something to carry and instructions and I would forget because they knew that I might be dyslexic. In the presence of my mother, they told me to open the door and go downstairs, but by the time I came up again, I forgot the instructions they gave me. Thereafter, the teacher told my mother, in my presence that I was backward. I discovered in my late thirties, when I went to college, that I was indeed dyslexic, with a short-term working memory and slow processing ability, and I have a psychological educational report to prove it. Though I was an average learner, nevertheless, I had the ability to learn, and I am still learning. My teachers chose me to play Angel Gabriel when I was six years old because they knew I had the talent, but they crushed my dreams of acting when they sent me to an ESN school, where I was not expected to learn, so I did not get beaten.

My autobiographies marked my victory over the objective of the racist education system.

Enlightenment comes to us at different time in our lives. At 30 years old, I migrated to Africa with my children to marry my fiancé because I did not feel I belonged here in Britain. I bid the late Queen of England goodbye, and I threw away my winter coat to symbolise the fact that I would never return to England not even for a holiday. The plan was to send for my mother. Once I arrived in the ‘Motherland’ in 1989, things were not going as I planned. I tried to write a letter to my mother for financial help to return home, but I struggled to write simple sentences or spell the words to describe what was going on. It was at this point that I realised that my problems were because I was illiterate, dull, and boring and I lacked confidence and self-esteem, which caused me to be depressed. I had nothing to offer Africa or even my partner, but worse of all, I had nothing to offer my precious children. So, with the help of my mother, I came back to England determined to learn to read and write properly and tell my story one day, but I did this at my children’s expense. After being moulded and shaped in an ESN school, I just could not work to provide for my children and study at the same time.

Exactly 30 years later, in 2019, I began to write my autobiography, not out of anger or frustration like back then when I was an illiterate person in Africa, but because I could, and I promised myself I would. My autobiographies, ‘Subnormal: How I was Failed by theBritish Education System’ and ‘A Colonial Family: The Windrush Generation’, marked my victory over the objective of the racist education system. By this time, I already had four degrees under my name, and published a book about my African ancestors’ resistance to slavery in the year of 2019: ‘THE TRUTH: How Africans Fought against Slavery from Their Homeland, upon High Seas, and Continued on the Slave Land’.

However, I did not realise that the climax of my life was fast approaching. Unbeknown to me, I was part of a scandal, and Steve McQueen was filming a documentary called ‘Subnormal: A British Scandal’, which would feature my story – a page in my book I didn’t know I had. Until the year 2020, I did not know that I was one of thousands of Black children who the education system deliberately placed into ESN schools. I thought I went to an ESN school because I was simply backward. I did not know [of] a great and wonderful man called Bernard Coard, who exposed the secret of what was happening to West Indian children in British schools, back then when he published his book. He gave us back our respect and equipped us with a voice to boldly speak out and write about this injustice one day, like I eventually did.

Coard’s book triggered a heated discourse in the Black community, prompting my mother to get me professionally assessed. Without Bernard Coard, Steve McQueen would not have been able to continue exposing the plight of West Indian children 30 years later, after he had published his book.

Boys and children from mixed or black ethnic groups are more likely to be excluded and go on to ESN School.

The arrival of the HMT Empire Windrush in 1948, initiated progress in combating racism in Britain, with the implementation of laws such as the Race Relations Act 1965 and the Equality Act 2010, in contrast to the Colour Bar of pre- and post-World War I. Now, it is common to see people from diverse racial backgrounds in jobs like, social work, banking, news presenting and entertainment. We even see Black and Brown ministers in the House of Commons, though there are claims of racism.

But, what about the education system? Has it changed? We do see more teachers and headteachers from ethnic minority groups working in schools, though like the House of Commons; The Guardian informs us that there is evidence of racism against Black teachers. However, the fact is, in 2001, according to The Guardian, the education system promotes racial segregation in schools, resulting in Black children being more likely to fail even if they are equally bright as their white peers. As recently as 2020, a UK-based charity that aims to improve the lives of children and young people with mental health problems, the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families, reported that, boys and children from mixed or black ethnic groups are more likely to be excluded and go on to ESN schools. It is important to stress that this is not the experience for every mixed-race or Black child.

I would not be surprised if the parents or grandparents of these children are descendants of ESN children, from the 60s and 70s, who left schools, like me, illiterate with hardly any social skills to have or to raise children. I mentioned previously that Coard predicted that our children ‘would look forward to a similar educational experience and similar prospects like ourselves’. Coard goes on to write, ‘No wonder E.J.B. Rose, who was Director of the ‘Survey of Race Relations in Britain’, and co-author of the report ‘Colour and Citizenship’, states that by the year 2000, Britain will have a Black ‘Helot’ class unless the educational system is radically altered.’

Rose was right, because recent years has witnessed the rise in the over-representation of Black and Brown presence (mostly Black) in the job centres, prisons, and mental health hospitals. This is why I said at the beginning that, ‘I am like a soldier who has won the war but wounded by the bullets of racism,’ and have come to share that experience with you. My lingering pain and wounds stem from the fact my experience of racism has greatly affected my children and delayed my development. which means I cannot retire if I want to. It wasn’t until my early fifties that I landed my first real job, as a dyslexia tutor, working for two years. It has become hard for me to find a job as I’ve gotten older, and my financial future looks grim.

It takes a whole village to raise a child.

My children have been to prison, and two of them have spent years in mental health hospitals. As a young family, we lived in poverty, and we never went on holidays. I was always studying and depressed which affected my children. I just could not take care of them, the way I ought to, and study at the same time. As Coard predicted, my two eldest children went to a special school. Though my third child did not go, he had a child with someone who did and now his son has recently started a SEN school. Parents are convinced that these schools are better now, but nevertheless, I did not want him to go to such a school that I believe should not exist today. Nothing has wounded me more than to know that my grandson is going to an SEN school. It takes a whole village to raise a child because that is exactly what happens when you send your child to school. You send them to school because you want strangers to help you to educate your child and in so doing, help you to raise them. And thus, teachers have the power and the tools to make your child achieve excellence or grow up to be worthless in society. Modern scholars tend to disagree with John B. Watson when he said:

‘Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in, and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist. I might select -doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations and the race of his ancestors.”

Watson believed that the influence of the environment could cause substantial changes in behaviour, even though an infant was born in a challenging environment and has diverse backgrounds or genetics. This is the power of a teacher. Have high expectations of all children, no matter the race, ability, and disability. Destroy racism in British schools because people of colour are not going anywhere.British Black people should have the same rights and respect like white people who refer to themselves as Australians, South Africans, New Zealanders, and the white West Indians whose ancestors were not natives of those lands, and their children deserve the best education.

Stop apartheid in the British school system and allow all children to learn and get to know themselves and be proud and celebrate their differences together. Take a leaf out of Bernard Coard and his wife Phyllis Coard’s book, ‘West Indian Children, Getting to Know Ourselves’ (1981). All children are special, therefore, there should be no special schools. Special schools make children feel different in a negative way and can affect their behaviour, in my opinion. Build larger schools with different departments to welcome all children and invest in teachers’ training, so they can tutor all children. When teachers educate children in the same building, they will become familiar with diversity from infant age.

Invest in Education!

For example, allow wheelchair users, the deaf and the blind, to grow and develop together at their own pace in schools. How beautiful it would be to see an abled body child go to school happily with a child in a wheelchair, to see a deaf child talk to a child who is not deaf through sign language, a blind child teach a child who is not blind empathy, patience, and creativity and how to think out of the box, good listening skills and how to appreciate the other senses, such as touch, smell, and sound, and to be more aware of their surroundings? According to Bernard Coard, in his time, all children learnt together in the same school in the West Indies. He said in the ‘Subnormal: A British Scandal’ documentary that he had never heard of ESN schools until he came to Britain. Therefore, it is possible.

Invest in Education! Patience, morals, and love is the building of a Great Village.

(c) Maisie Barrett, 2024

Bibliography

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/School_corporal_punishment

- Blad, L (2019) Thousands of mixed-raceBritish babies were born in World WarII – and adoption by their black American fathers was blockedhttps://uk.news.yahoo.com/thousands-mixed-race-british-babies-095731264.html

- Coard, B (1971) How the West IndianChild Is Made Educationally Sub-normal in the British School System: The Scandal of the Black Child in Schools in Britain.NewBeacon for the Caribbean Education andCommunity Workers’ Association, p.20

- Coard, B (2005) Why I wrote the ‘ESN bookhttps://www.theguardian.com/education/2005/feb/05/schools.uk1

- Coard, B (1971) How the West Indian Child Is Made Educationally Sub-normal in the British School System: The Scandal of the Black Child in Schools in Britain. NewBeacon for the Caribbean Education and Community Workers’ Association, p.19

- Ibid., p.21

- Ibid.

- Parveen, N, McIntyre, N (2019) ’Systemic racism’: teachers speak out about discrimination in UK schoolshttps://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/mar/24/systemic-racism-teachers-speak-out-about-discrimination-in-uk-school

- Asthana, A (2016) Britain becomingmore segregated than 15 years ago, saysrace experthttps://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/23/britain-more-segregated-15-years-race-expert-riots-ted-cantle

- Coard, B (1971) How the West Indian Child Is Made Educationally Sub-normal in the British School System: The Scandal of the Black Child in Schools in Britain. NewBeacon for the Caribbean Education and Community Workers’ Association, p.10

- Watson, J. B. (1930) Behaviorism Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

- Sacks, S. Developing Social Skills in Children Who Are Blind or Visually Impaired https://www.perkins.org/resource/developing-social-skills-children-who-are-blind-or-visually-impaired/

- Subnormal: A British Scandal (2021) https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000w81h

Maisie Barratt is an author, playwright and political campaigner. Connect with Maisie here.