CROSSING CONTINENTS

This community-led research project explores how the folk scene has been informed by Afro-indigenous stringed instruments.

Community researchThe journey of the banjo instrument, brought from West Africa to the Caribbean and the Americas by enslaved people, is not a widely know story outside of the collections specialists and academics. Today, the banjo and the folk music scene are typically associated with white western culture.

‘Crossing Continents: Collections Research as Resistance‘ was a community-led project that brought musicians, organisers and researchers together to challenge those assumptions, to share the origins of the banjo more widely within Black African and Caribbean communities and to offer new potential for self-determination by contemporary Black folk musicians working in primarily white spaces.

We need to bring this research to the community. It’s all so held in this fortress.

Marcus MacDonald

‘Crossing Continents: Collections Research as Resistance‘ ran from April to July 2025. The project’s co-researcher team comprised of banjo player and one half of folk band The Pegwells, Bianca Wilson; singer, multi-instrumentalist and songwriter, Angeline Morrison; and queer punk, grower, community organiser and tour manager, Marcus MacDonald.

Convened and sponsored by Carey Robinson, Deputy Director, Learning & Public Programmes at the Fitzwilliam Museum, and funded by the Collections, Connections, Communities research initiative, over three months the co-researchers hosted an afternoon of discussions with researchers at the Fitzwilliam Museum; explored the archive of English collector of folk songs and instrumental music, Cecil Sharp; visited the University’s Botanic Garden; explored the Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology‘s collections store; threw a social gathering in south east London at the Land In Our Names (LION) community garden; and recorded a podcast.

Much of this journey has been captured by filmmaker Dee Iskrzynska, whose short film will be made available here in the coming weeks. The podcast will be broadcast on NTS Radio this summer.

I play the banjo, and a lot of people often ask why I play the instrument, because it’s not really something that’s associated with Black people, which is completely wrong.

Bianca Wilson

In the planning stage of the project, Angeline talked about how folk music’s association with whiteness erases historic Black presence in Britain:

‘I’m particularly interested in sharing knowledge and helping shine light on misconceptions about the historic Black presence in Britain and our involvement in the folk song and folk music of England and of these islands more generally, because we have a historic presence here that dates back at least to 2000 years, people of the African diaspora. Yet in the context of the folk music of Britain, these are coded as very white; and Black history, Black culture, Black musicians, Black stories and Black material are mostly absent.’

The idea of cultural codes and the ways they are upheld through coded language is important. Language conveys subtle or implicit messages that reinforce outmoded social norms, biases and power imbalances – these stereotypes are pernicious and need to be challenged and destabilised. As Bianca says:

‘As a Black musician in the UK, it’s very difficult to exist outside of the urban or soulful category, and even when you do, your music is going to be described as urban and soulful jazz by the listeners, because we’re so obsessed with the idea of a racialised sound that I genuinely believe that people are experiencing the music in that way. I think they are hearing soul music when it’s not, because the singer is Black. I guess it’s just about like dismantling the ideas that we have of that separation, and understanding why it exists is key to unlearning it; and we do that by highlighting what that sound is and presenting and showing people [the banjo].’

There has been a long story of Black cultures being under scrutiny from white observers and collectors and archivists and historians.

Dr Ross Cole

The co-researchers hosted a series of in-depth conversations at the Fitzwilliam Museum during April, meeting Dr Eva Namusoke, Senior Curator, African Collections Futures; Dr Alisha Lola Jones from the Faculty of Music, University of Cambridge; and Dr Ross Cole, author of ‘The Folk: Music, Modernity, and the Political Imagination’ and Associate Professor of Music, University of Leeds.

These conversations helped us to consider how music traditions, cultures and instruments, when shaped through an academic lens or stored out of their original context – untouched in boxes in the archive – fall out of reach of wider and source communities. Eva shared how her painstaking African Collections Futures research project, undertaken over 15 months, documents where Africa-related objects and materials are held across the University of Cambridge and who engages with them. While that project underscored the University’s aspiration to become more permeable as an institution, it was also sobering to learn how many tens of thousands of objects and artefacts from the African continent the University has taken ownership of – too many to document.

The collections they hold are, as any archivist and any historian will know, subject to the power dynamics of those who made them and maintain them.

Dr Ross Cole

Alisha was encouraging about the opportunities that access to the University of Cambridge collections offered and urged us to retain criticality. ‘I tell folks these projects are about consumption… how we take for granted access to Black Bodies.’

The value of criticality was underscored by Ross, who reminded us how important it is to bring questions from the community to the archive – it’s these questions that may challenge perceptions, and over time help to shift the ways orthodox academic researchers and funders uncover knowledge:

‘The collections they hold are, as any archivist and any historian will know, subject to the power dynamics of those who made them and maintain them,” he said. “There’s a real sense that the banjo belongs to the history of whiteness, and it’s a complete and deeply ironic betrayal of that transatlantic story. There’s plenty of work to be done bringing that to the fore again.’

After these rich and inspirational discussions with Eva, Alisha and Ross, the objectives for Crossing Continents were further refined and clarified:

Objective 1: To increase access to the collections for people from the African and Caribbean diasporas in the UK.

Objective 2: To raise awareness of the West and Central African origins of the banjo through a diasporic historical lens.

Objective 3: To expand perceptions of which sounds are constitutive of Black music.

In May, as part of the Fitzwilliam Museum Late: Future Legacies (see more about Museum Lates here), Bianca performed with her band The Pegwells, and also brought along a very special surprise guest from New York, Jerron Paxton.

We circulated a very simple baseline survey to take a snapshot of the Cambridge audience’s perceptions about the banjo and its influences. We received 57 responses during the two 45-minute sets with The Pegwells and Jerron Paxton.

Headline stats:

- 63% of people answered ‘No’ to the question, Have you ever heard of any Black folk musicians in the UK?

- 60% of people chose ‘Africa’ to the question, Where do you think the banjo originated? (the other options were America, Scotland or Ireland, other).

- 55% of people replied ‘Yes’ to the question, Has today changed how you think about folk music or who it belongs to?

- Almost three quarters of people replied ‘No’ or ‘Maybe vaguely’ to the question, Before today, were you aware of any African or African diasporic influence on British or American folk music? (just 11 people said they were aware of African or African diasporic influence before the performance).

We were initially surprised that so many people were aware of the origins of the banjo (question 2), however, we realised that the audience was a typical audience for the Fitzwilliam Museum, which is predominantly white, affluent, and highly educated, which could indicate an academic awareness of the origins of the instrument.

The responses were less surprising in relation to the lack of awareness of Black folk musicians in the UK. We were interested to see that over 50% of people felt the event had changed how they think about folk music or who it beings to, with almost 75% saying they had not been aware of African or African diasporic influence on folk music before the performance.

This data was useful in offering a baseline and underscored the need for the work as outlines in our objectives: to bring knowledge typically sequestered away in hard to access archives to wider communities of colour; to bring lived experience perspectives to that knowledge; and expand notions of what constitutes Black music.

I view the banjo as emblematic of gastro-ethnomusicology. The fact that it’s made out of the gourd, a food.

Dr Alisha Lola Jones

Eva had confirmed that the Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology collection held a number of stringed gourd instruments – this was especially interesting to Marcus, who has a growing practice and is a member of the Land In Our Names (LION) collective. Marcus has grown and cured some gourds that he hopes to transform into gourd banjos (Watch Marcus and Bianca conversation about gourd banjos and resistance on the Future Legacies site here).

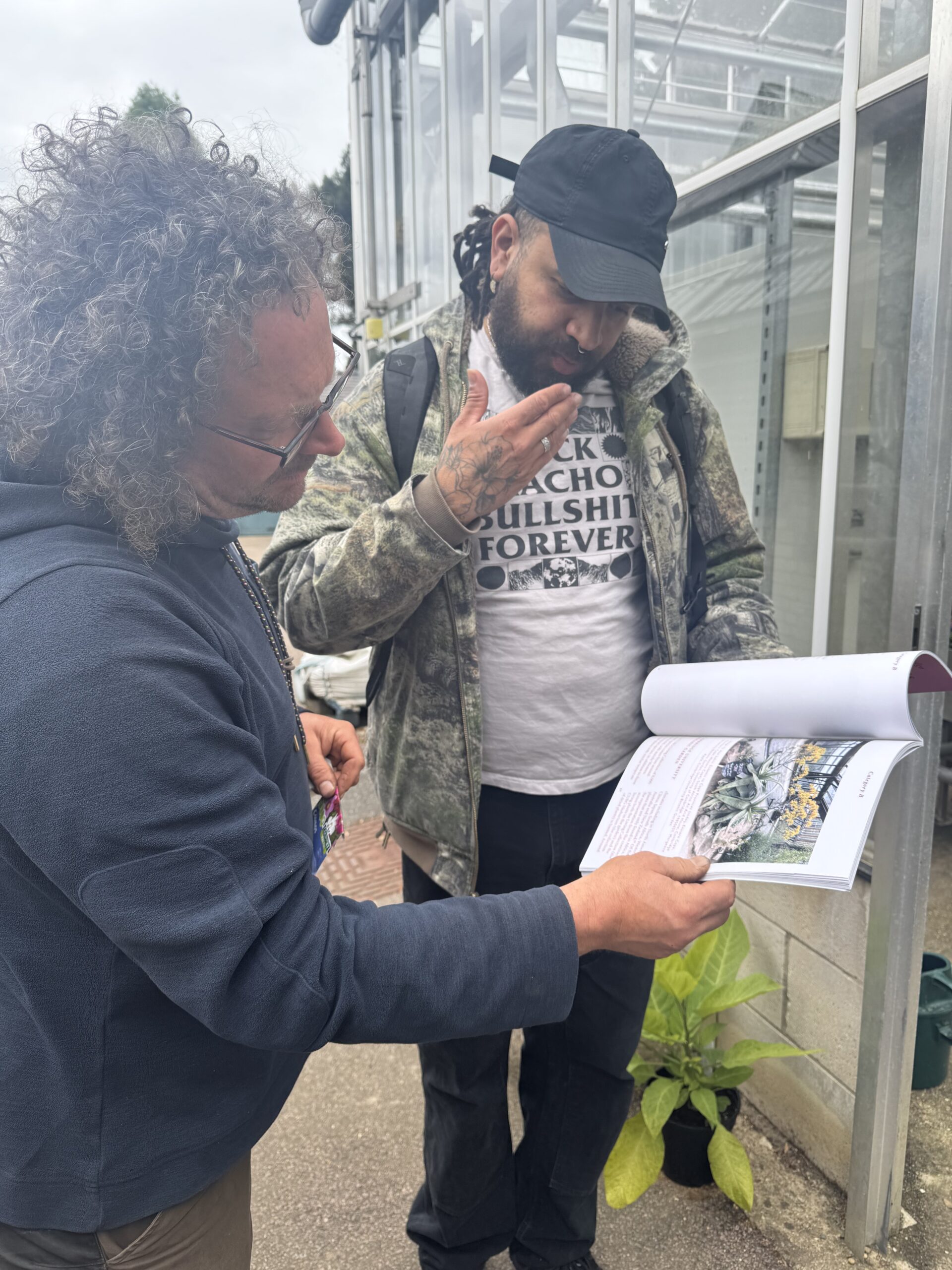

In May, Marcus and Bianca visited the Cambridge University Botanic Garden, where they met horticulturalists Peter Wrapson and Jon Strauss to exchange knowledge about the inception of collecting plants as part of the colonial project, growing and gourds, including how, during the transatlantic slave trade, enslaved women hid seeds in their hair in order to preserve and transport valuable food sources, enabling them to cultivate and grow crops after being forcibly removed from their land.

With the birth of genre and racialised musical categories, Black is singular and often for the purposes of commercialisation. But this [project] is about expanding ideas of Blackness and Black sound and giving people that freedom to choose aspects of what they want to be, that [the banjo] comes from where they are from.

Bianca Wilson

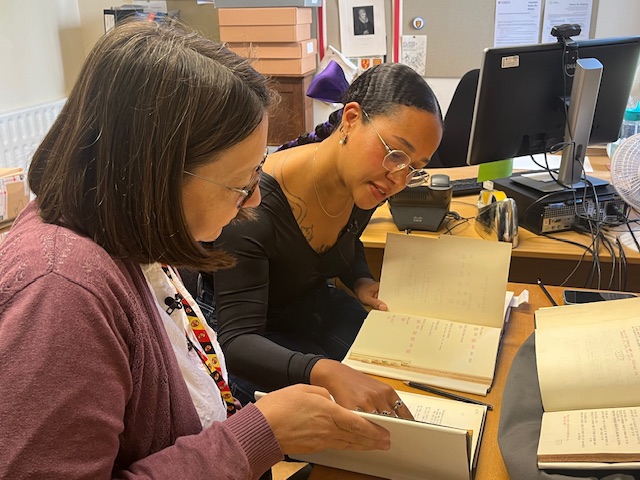

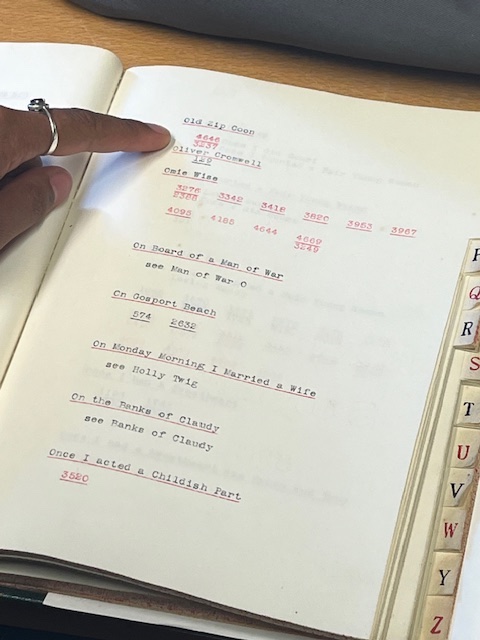

In June, Bianca and Angeline travelled to Clare College, Cambridge, where the Cecil Sharp archive is kept. Cecil Sharp (1859-1924) was a leader in the English Folk revival. He became well known for his prodigious collecting of folk songs, which took place on his many trips to the Appalachians in the USA. Sharp launched the English Folk Dance Society (EFDS) in 1911, and helped to get folk music into the school curriculum.

While Sharp preserved oral traditions by writing them down, he refused entry of Black musicians into his collection, leading to criticism about his selectivity in deciding what to collect, his treatment of informants, and the relative importance of oral and printed sources of songs. His fascinating archive included music notebooks comprising hand written manuscripts of folk words, folk tunes, folk dance notes, ballads and songs and even illustrations of dance steps.

Angeline and Bianca, sight reading from music scores, each chose something to sing from Sharp’s notebooks, bringing the archive alive in ways the archivist had not been able to experience before. The relationship with Sharp is complex: his efforts were crucial in safeguarding oral folk traditions, yet they were underpinned by racist beliefs that continue to raise important questions about legacy and interpretation.

If you remove the ability [of instruments] to make sounds, then you strip them of something that’s essential to what they are.

Dr Eva Namusoke

Bianca, Angeline and Marcus spent a day together at the Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology‘s collections store at the Centre for Material Culture in Cambridge, where they were shown around by Rachel Hand, Collections Manager (Anthropology), and Rosie Croysdale, Senior Education and Outreach Assistant, who had together carefully retrieved and laid out an array of objects and instruments selected in advance by Angeline and Bianca via the online collections database.

We had wondered in advance whether playing or even touching the instruments would be permitted, given their age and fragility. An instrument is designed to be played – what happens when it’s kept boxed up and unplayed for decades? We had discussed this at the start of the project with Eva: ‘If you remove the ability [of instruments] to make sounds, then you strip them of something that’s essential to what they are.’

At the Centre for Material Culture, the instruments Rachel and Rosie had laid out included zithers, mbira’s, and stringed instruments crafted from gourds, animal skins and tortoise shells. Rachel concurred that many instruments in the collection were too fragile to be played, although we were able to handle them. The mbira had not been played since 1938, and Rachel invited Angeline to play it with care for a short time.

Rest, restoration, restoring, restitution.

Angeline Morrison

We want to get more Black people into folk, playing banjo’s, building banjos and away from the idea that it’s a white thing.

Marcus MacDonald

Folk is a social music that facilitates the gathering of people – during June’s sudden heatwave, Bianca hosted a banjo workshop at a social gathering in the Land In Our Name (LION) community garden, creating a historically accurate context for the research.

The LION birthday gathering was for Black and People of Colour/Global Majority. This was significant because, as Bianca tells us, ‘there is a big narrative of reclaiming this history of the banjo in the US, but we don’t have that here in the UK.’ Assembled together in the garden that evening was part of the reclaiming of that history in the UK context.

The community garden is on the edge of Burgess Park in Southwark and, in June, was filled with abundant, scented foliage and shrubs, vegetables, trees bursting with purple and yellow plums. Food and drinks were served, adding to the convivial atmosphere, and people congregated on wooden benches and railway sleepers around a fire pit. More than 15 people picked up a clawhammer banjo, a guitar, percussion instruments or spoons, and experimented with slapping, plucking, strumming and picking under Bianca’s direction, with a final group performing a song together beneath brightly coloured bunting as the sun lowered beneath a pink sky.

When people ask, ‘Why are you singing this material?’ what they actually mean is, what are you doing as a Black person singing white people music. That’s what they mean. They don’t come out and say that because they’re generally polite and friendly people, but you can read that. You can read the energy of the question.

Bianca Wilson

As the evening drew to a close, Bianca and Marcus shared the purpose of the Crossing Continents: Collections Research as Resistance project, which raised cheers and acknowledgement from the enthusiastic crowd.

‘When people ask, ‘Why are you singing this material?’ what they actually mean is, what are you doing as a Black person singing white people music. That’s what they mean. They don’t come out and say that because they’re generally polite and friendly people, but you can read that. You can read the energy of the question.’ This social gathering of Black, People of Colour/Global Majority people playing folk music and the banjo together removed that question.

To culminate the project, the co-researchers are recording a podcast with invited guests including Dr Ross Cole, multidisciplinary artist, multi-instrumentalist, researcher, Dr Hannah Catherine Jones, and singer-songwriter and researcher, Marie Bashiru. Together they will examine the tensions and oppositions, the confluences and synergies of this research project. The podcast recording will be made available for this site, along with the short film about the project.

The banjo has been transformed from an instrument of African origin, into a product of white musical knowledge and ingenuity. This project offers a form of redress.

Carey Robinson

We are seeking to begin a Black British folk revolution.

Angeline Morrison

Bianca Wilson is a banjo player, musician and one half of folk band The Pegwells. Follow Bianca here.

Angeline Morrison is a singer, multi-instrumentalist and songwriter. Listen to Angeline’s work here.

Marcus MacDonald is a grower, queer punk, and member of Land In Our Names collective (LION). Connect with Marcus’ practice here.

Dr Eva Namusoke is Senior Curator of African Collections Futures at the University of Cambridge. Find out about Dr Namusoke’s research here.

Dr Alisha Lola Jones is Associate Professor of Music in Contemporary Societies at the University of Cambridge. Learn more about Dr Jones here.

Dr Ross Cole is an Associate Professor of Music at Leeds University. Read about Dr Cole’s book here.