BLACK LENS: KNOW YOUR CARIBBEAN

‘Know Your Caribbean”s Fiona Compton and UK Black History educator Kayne Kawasaki unpack a Cambridge exhibition to explore Caribbean histories.

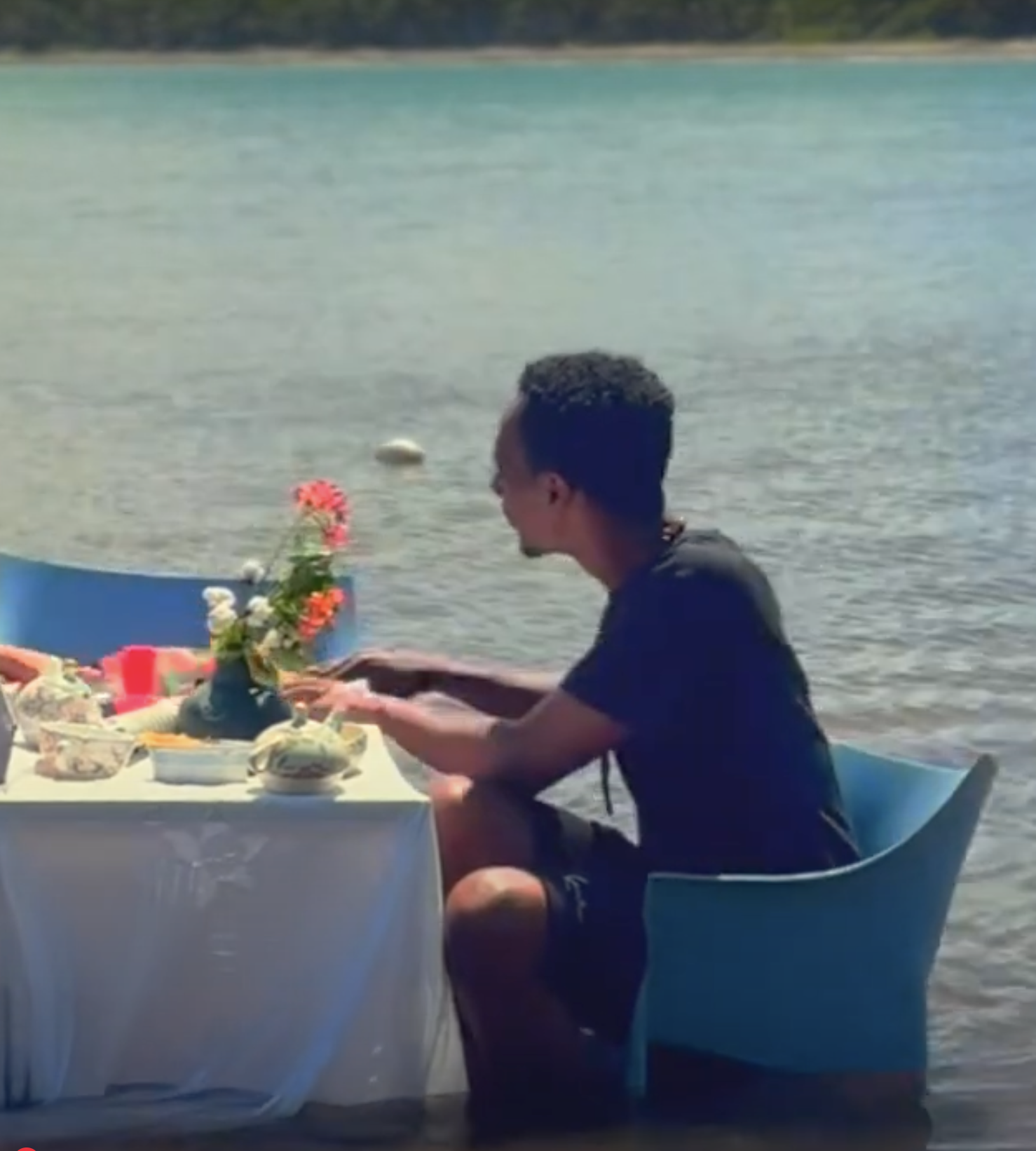

InterviewsJoin Fiona Compton and Kayne Kawasaki for an Atlantic sea party and take a deep dive into rich and surprising themes from the Fitzwilliam Museum’s 2023-24 ‘Black Atlantic: Power, People Resistance‘ exhibition.

This conversation is dedicated to the memory of our ancestors from the Black Atlantic.

Know Your Caribbean: Well, thank you for coming to this little tea party, it’s an honour to have you here in St Lucia, here in this space, it’s a really powerful space. I wanted to bring you somewhere that has a lot of history, when we speak about the Black Atlantic.

Right now we are sitting as two Black people in the Atlantic. We’re gonna have a little tea party because we have a lot of links to this history. A lot of the things we grew up with, you know – having a cup of tea – but um, I just wanted to thank you for the work that you do, as an activist, as a historian, specifically a Black historian and sharing the stories in the way you do. But, what brought you to this point where you are now?

Kayne Kawasaki: Yes, thank you for having me, first and foremost. It’s a bit of a surreal experience sitting as two Black people, in the Atlantic, so I do want to acknowledge that and take it in and advise others to do so as well, especially, you know, having this conversation. And the Atlantic spreads throughout so many different countries, so if you do have the opportunity to do so, sit in it and really kind of manifest and think what that term means.

But yes, my journey. I’m from southeast London, Peckham to be precise, and my heritage is Jamaican. I was always taught to be a lover of history, in particular pan-African history. And, from a Jamaican background, I’m sure a few people can kind of identify with Ethiopia and Halie Selassie and Marcus Garvey and those kind of teachings. And it just never really stopped from there. Growing up, I loved history, and I was actually advised not to take history. I was advised not to take it because I was told it wouldn’t go anywhere. So, as a result, I took English instead, and then as a result I ended up becoming a teacher. Lo and behold, now what I do on social media is teach about history, but, outside of the confines of my four walls, which is kind of what my purpose was. But people kind of put me in the box of just being a teacher, and I think often when you think about history it’s within that box. Whereas essentially, history needs to be outside of those four walls.

KYC: Absolutely! That’s how I feel. I dropped History in secondary school as I found it boring, I didn’t connect to the emotional side of the story. But I think this is a way for us to speak about the Black Atlantic, and how we connect to that history. As we have our conversation, I’d like you to help me set up this table. So in this bag here, we have our tablecloth, which is made from cotton, and if you have a look in the bag you’ll see there is some…

KK: I’m excited.

KYC: You’ll see there are two [flowers] in there.

KK: I saw you pick this.

KYC: Yes! So what are your thoughts on these two pieces?

KK: Yes, the first one got… because of its colour it got a positive reaction from me. The colours are pink and green and life and all the semiotics that go with the colour of pink. And then, the second one is white and brown, and it looks like, it invokes a certain emotion in me…

KYC: Do you recognise the two pieces?

KK: I recognise one out of the two.

KYC: The obvious one! Which of couse is cotton. Cotton was growing just around the corner from where we’re sitting. Actually we’re sitting in a place called Cotton Bay, and the local name for that we say ‘Cas en Bas’. The other flower is called a peacock flower. And within the [Fitzwilliam Museum’s] ‘Black Atlantic’ exhibition there were some illustrations by this botanist [Maria Sibylla Marian] who came from Germany, and she went to Surinam – what struck you about her work in that exhibition?

KK: I don’t remember specifically, but I do remember seeing that flower, and it’s interesting because for me, it actually links to an experience that I had recently when I went to St Vincent and was looking at their botanical garden, and I saw the same thing. So for me, once again, the Black Atlantic, it’s just making those connections between the botanists and then actually being on the ground and physically seeing it and being at this table now, it feels like a full circle moment. Both seeing the peacock flower in person, seeing it in the exhibition, and then seeing it in another Caribbean country as well.

I feel like the smaller acts is where the power really is.

KYC: We are going to get to St. Vincent and the botany and the gardens there. From that illustration, one of the she has done is she accessed the knowledge of indigenous and enslaved people in Surinam to understand and have a wider knowledge of botany. Amongst those illustration was this which is the peacock flower. It’s very interesting that you said that, looking at the peacock flower, you said that it gave you life, the colours – and it was used by enslaved and indigenous women to end their pregnancy. Because they said they were so cruelly treated by the Dutch enslavers that they did not want their children to live a life of enslavement. We look at the flower, we see it’s so vibrant and beautiful but they used the seeds to secretly end their pregnancies. What are your thoughts on those kind of forms of silent resistance, of Black resistance, we often think the big, the bold, the Toussaint L’Ouverture, the Haitian Revolution, Nanny the Maroon – what are your thoughts on these smaller acts of resistance that you don’t hear so much about?

KK: I feel like the smaller acts is where the power really is, as you mentioned, sometimes the story tends to be focused on those big grandiose moments, but those smaller moments of people taking control of their agency. I think also as well, that goes to show the importance of history. Because, from me looking at the flower, first I was talking about the semiotics and the connotations, and often I’m assuming that’s what people would do when they would walk into an exhibition, right? You would see the exhibition and then you naturally want to react before you read the information. But it’s almost like you have do it the other way around, you have to read the information and then react. Because, like I said, although this flower is pretty and it’s pink, it has a story attached to it, so it almost provides that oxymoron, which I suppose is the oxymoron between being Black, and Atlantic, and the idea of what that presents. And also as well, I think it’s important to refer to the exhibition in its full name, ‘Black Atlantic, Power People Resistance’. And, that’s the part of the exhibition that I felt like the people were highlighted, I feel like the power was highlighted, but I feel like the resistance could’ve been just a little bit more pushed, and that’s my personal opinion.

KYC: Absolutely, even on this flower, there could’ve been some more expansion that that was an act of resistance. These are the silent forms of resistance that are as important as the big, grandiose forms of revolution that happened. This was more of an everyday occurrence where instead women would use these as a contraceptive or to end their pregnancy. That’s pain that they had to carry silently and it’s pretty much undocumented except for this small sentence in her book of so many illustrations. I mean we can speak all day about the cotton!

KK: We can!

KYC: When we’re having these conversations about Britain’s legacy with enslavement in particular, I think there is little acknowledgement of how it expanded into the very fabric of Britain, and looking at the cotton industry as well – when we look at Hollywood films and depictions of slavery, cotton is always associated with America, but not the UK. What are your thoughts about how expansive the cotton industry was in the UK, and how little acknowledged it is, in terms of its links to slavery?

It’s really important for us to understand that cotton is very much British history as well, it’s not just the American cotton pickers that you see in the Hollywood films.

KK: Cotton for me is such a big topic and I do feel like there is very little acknowledgement and that is because of how Britain has set up their thing, as opposed to America. Obviously, a lot of the cotton was outsourced and kept away and kept out of people’s eyesight. So, when the cotton was arriving in Britain, and obviously part of that is to do with climate and topography and things of that nature. Because, obviously Britain can’t grow cotton and as a result it’s almost like they’ve grown an ignorance in the people. Because, by the time the cotton it comes to us, it’s in our factories in Manchester… largely people from Britain are ignorant. And that’s not just a race thing, I feel like that supersedes all of the different races who grow up within Britain because, it’s not something that we’re used to seeing. So as a result, when these conversations do come up, we’re like, ‘Why is that important?’ But, even when you don’t look at just the history, even when you look at the contemporary, there’s still conversations around our clothing and how they can be reused and recycled and the impact on the environment. And, I find it quite disingenuous that we can have those conversations so powerfully now, but we can’t have the same powerful conversations when we’re talking about the history and the legacy.

KYC: As you said, the cotton industry in Manchester is huge, but it’s so vastly unknown, and when you understand how it funded so many things like, you know, the Manchester Train Station. It’s really important for us to understand that cotton is very much British history as well, it’s not just the American cotton pickers that you see in the Hollywood films.

KK: And talking about even the cotton of present day, in Jamaica, once again there’s a very specific strand that’s grown, still grown [Jamaican Sea Island cotton] and once again, a lot of that cotton isn’t benefitting the local people. It’s one of the finest cottons in the world, but then once again, you know, it’s still being grown, it’s still being used for clothes, when you look at the Queen for example, and a lot of her cotton that she has, it’s from this [Jamaican Sea Island] cotton. But it’s not benefitting the local people. And, you know, I say that to say essentially history is continuing, and that’s why it’s so important for us to have both the history but contemporary as well and acknowledge that it’s still happening.

KYC: That is a wonderful nugget of information.

KK: I think that that same strand is grown in Barbados [and Antigua] as well.

I have fond memories of breadfruit, especially coming from a household that favours an ital diet and things of that nature.

KYC: Barbados is another piece of everything. Before we have some of our tea, I would like you to have another dig in our bag of curiosities.

KK: This one?

KYC: Yes.

KK: This one needs two hands!

KYC: Yes. I picked this this morning, in my garden.

KK: Ah, this is in your garden? Nice.

KYC: It’s tall, right. Can you tell me what this is?

KK: Yes, breadfruit.

KYC: Yes, yes, and the history of breadfruit was a movie. There were several movies about breadfruit – well it wasn’t really about breadfruit it was about Captain Bligh and the mission to transport breadfruit from Tahiti to Jamaica. What are your thoughts about when you look at breadfruit’s journey from Polynesia and then travelling across the world and landing in St. Vincent in the 1770s? Can you tell me a bit more about when you visited the St Vincent Botanical Gardens, which is the oldest botanical garden in the western hemisphere?

KK: Yes, sure. The first thing that I would say is that the Botanical Garden is very beautiful in St. Vincent. And, when I say beautiful that encompasses the local people, the knowledge of the local people, the history from the local guide; he was very knowledgeable. He said that his father had done it and the legacy of him now doing it. So, I would recommend people go and see, but once again it’s kind of like, you’re there and you’re looking at the colours and the well-maintained beautification of the botanical garden… it’s almost like the oxymoron between I have fond memories of breadfruit, especially coming from a household that favours an ital diet and things of that nature, often it’s used as a replacement. So, for me, it’s a thing of substitution and sustenance, but then once again you can’t ignore the history and the way how it was brought over and the way how it was cultivated and the way it was used.

KYC: And why.

KK: And why, so yes, for me, once again, it brings about fond memories but then knowing that those fond memories weren’t birthed from fond memories for everybody – and people who look like me historically.

It has cinnamon, nutmeg, coconut milk, some vanilla. Cocoa was very much a part of something in terms of amassing the wealth in the UK and in Europe as well.

KYC: Absolutely. In the exhibition I saw there was an illustration of a breadfruit tree, by an artist John Tyley. What are your thoughts about John Tyley, as an artist? You don’t see artists of colour being in the forefront of representing things that happened in the Caribbean.

KK: Yes, he’s a much-needed voice in terms of representation, and it just gives a different perspective as a person of colour. And, once again, the title ‘Black Atlantic, Power, People, Resistance’, he very much is a person that without his voice it wouldn’t have been the same.

KYC: It was very ballsy for that era for a [botanic artist of colour] to sign his name. If he hadn’t signed his name you wouldn’t have known who it was. And again one of the frustrations I have is that you find these amazing stories about these people and then they just kind of disappear and you don’t know what happened to them. John Tyley was contracted, he was a man of mixed heritage from Antigua, his artistic abilities would have been known for him to have been sent to St Vincent to document the gardens – and after that he just disappears, this incredible artist. For me that’s the hardest part of the history, these unanswered questions…

KK: Most definitely.

KYC: So – just pour yourself a cuppa, but it’s a different cuppa. It’s made from all local ingredients, but you will know it as a Jamaican. What is in your teapot?

KK: You know, I’m not much of a tea drinker, so I can’t pinpoint exactly what it is.

KYC: It’s cocoa tea, it’s unrefined chocolate.

KK: Ah. I love that.

KYC: It has cinnamon, nutmeg, coconut milk, some vanilla. Cocoa was very much a part of something in terms of amassing the wealth in the UK and in Europe as well. There’s a lot of focus on sugar but cocoa is something that our ancestors had to harvest. In St Lucia particularly there are a lot of cocoa plantations that still exist today. So I just wanted to honour our ancestors by having some cocoa tea.

KYC: So we just had some cocoa tea, right? Now a lot of things that we do in St. Lucia, the St Lucian way, is on a rainy day we will put a little something in our cocoa tea. So I have something here that I’m going to dip, would you like a dip?

KK: Yes, yes, most definitely!

KYC: Just a little something. So what is the name of this rum?

KK: Equiano.

This is a Black-owned rum, one of the very few.

KYC: So we know that this is a Black-owned rum, one of the very few. I thought it was good to have this here with us, and how did the exhibition respond to [Olaudah] Equiano’s story?

KK: Often, the story is told, but often confused. So, there are different depictions of who he is, and who he isn’t and is that him, is that not him, which speaks a little bit about what we were speaking about earlier. The fact that, you know, just having that little bit of acknowledgement, or where it ended, or how it ended, or where it began. So yes, speaking broadly, there is information out there, there is quite, in my opinion, a lot of information out there. But often, it’s not precise and I’m pretty sure that was probably reflected in the ‘Black Atlantic’ exhibition.

KYC: One of the things I read up last night, is that in the Bahamas they found 14 sunken ships, and one of them was a ship he was transported on. He was a merchant as well in his later life, and he used to sell rum. So I just want to toast to Equiano, and everything that he did, now that we have a Black-owned rum that’s made in his honour. I love it. You see in a lot of old paintings, a thing that’s placed on the mantelpiece as a signifier of wealth, hospitality, is this very exotic fruit, what is that?

KK: The pineapple.

KYC: The pineapple!

In the ‘Black Atlantic’ exhibition there was a painting of a pineapple. Historically, the pineapple was encountered by Columbus in Guadeloupe for the first time, it became the signifier of exoticism, if I have a pineapple on my mantelpiece, I have money. There is in [the Fitzwilliam] collection, in [Matthew] Decker’s collection, there was a painting that was commissioned and it was a painting of the first pineapple grown in Britain. This is also highlighting Cambridge’s direct link with this history, and that Decker was what, a director of the East India Company, a governor of the South Sea Company, he was inextricably connected, he was one of the people who shaped one of the largest slave trading businesses in history.

Looking at how the generational wealth that was acquired through the Fitzwilliam collection, and seeing that the pineapple was a signifier of wealth.

Looking at how the generational wealth that was acquired through the Fitzwilliam collection, and seeing that pineapple was in that and that it was again a signifier of wealth, and also the first pineapple to be grown in Britain, so that they had these botanic gardens, this required wealth, this required finance to do that. Pineapple is a thing that we consider Caribbean, that is indigenous to the Caribbean, so came up from South America, moved up by the indigenous peoples. Things like coconut does come from the Caribbean, things like mango does not come from the Caribbean, those things have come here through like Captain Bligh and the breadfruit, through colonialism and these expeditions, the Royal African Company – and these are things we’re now seeing in the collection at Cambridge.

KK: Yes.

KYC: My mum is a collector. She bought something on eBay and I wanted to show it to you.

KK: Wow… your mum is definitely a collector [handles a Barbdoes Penny]. Wow. And do you know what’s interesting, is that on this side obviously, we’ve got someone adorning something of royalty, and what’s interesting is that when you were speaking about the pineapple, what came to my mind is that the indigenous people that are depicted on the Jamaican crest, where they’ve got a pineapple next to them… even the idea that it’s something of wealth, has almost been carried from the indigenous to the colonial…

KYC: Yes! It has different names, but in different places it is called the Slave Penny. This was the first coin to be issued in Barbados in 1788 and it was issued by an enslaver called Philip Gibbes. It has a depiction of a pineapple on it and it has a depiction of a Black person that has this regalia on, he has a crown, he has feathers. And what does it say on the bottom of it?

KK: On the bottom it says, ‘I serve.’

KYC: There’s lots of conflicting histories or theories about it, that it was made to be as a parody. That he’s wearing the Prince of Wales crown on his head, but what are your thoughts about that penny, given that it was the first coin to be issued in Barbados and there’s a Black person’s face on it, when a lot of the currencies in the Caribbean, especially the Eastern Caribbean dollars, still has the queen’s head on it?

One side of an old Barbados Penny showing a pineapple

One side of an old Barbados Penny showing the head of a Black man

KK: Yes, so my first thought was, you know, addressing the history and the idea that it could potentially be a parody or a joke or to poke fun. But, I would say that the joke is on them [laughing], because we know from whence we came, and we know thyself, and we know that this is not just a depiction of one man, we know it’s a depiction of many. Many men like him, and women, if you look at the history of Angola for example, or people who were and are royalty. So yes, seeing this in my hand, Black Atlantic, the word power comes to my mind. They intended it to be perhaps a parody, but to me I see power.

KYC: Yes.

I feel like by holding this coin, I’m holding a little bit of our history.

KK: And, it’s an amazing thing to have and to behold. And, often, you know, I often say, if you want to see your history, or get to know your history as a Black person, where do you go? The history, be it negative, or ugly, or perhaps beautiful, where do you go? And, if you think about other communities, so for example when I went to go and see the concentration camps in Poland, that’s a place to go. Other than Elmina Castle in Ghana, I can’t necessarily think of a place for Black people to go to view your history in its entirety. And, I feel like by holding this coin, I’m holding a little bit of our history.

KYC: As you said, you see power. I think that’s one of the important things. I find a lot of power in books written by all of these racist white men, these things they say that are so disparaging. I was reading a book yesterday by Charles Darwin and he said, that the Negros are so idiotic and they play this drum and its this monotonous pounding. Yeah, we do! The drum is our heartbeat, the drum is transcendent, it takes us somewhere else. It’s so powerful, and he see it as ridiculous. All he’s doing is cementing what I already know about myself, I know that my ancestors from 200 years ago when he wrote that book are feeling the same things that I feel today.

So you know when we talk about where do we find our histories it is in the pineapple, breadfruit, in the cotton, in the peacock flower, the cocoa, in the rum and in all of those little corners. I want to encourage us to continue to disrupt institutions and for us to not feel that we don’t have a place in these institutions, because we are the very foundation of these institutions, financially, historically…

KK: Even in terms of just the collection and the items.

Knowing the first peoples that were here, they lived here, they flourished here, and this spot was very sacred.

KYC: Yes. So to close off, I wanted to bring you to this beach not only because we’re sitting in the Atlantic and it is called Cotton Bay, but also, because around the corner is an indigenous peoples’ burial ground. And one of the things that was touched on in the ‘Black Atlantic’ exhibition was the indigenous artefacts. I’m thankful that there was recognition of indigenous peoples in the Caribbean, because they were very much part of the story, and still are, and we’re round the corner from a sacred burial place, and still feels sacred when you come here on certain days. The first peoples that were here, they lived here, they flourished here, and that they felt this spot here where we’re sitting was very sacred. I just wanted to acknowledge that.

KK: Yes.

KYC: Thank you.

KK: Thank you, thank you. I think often when we talk about Black history, there is almost a disconnect and the disconnect being that the two things can’t exist at one time. We have to appreciate the fact that, yes, you can go and see the exhibition in Cambridge, that’s the secular. But, you also need to come to the Caribbean and to Africa and connect and get the full story because that’s the sacred. And, that’s what we’ve been talking about, even when you mentioned about the writer talking about the drum. The reason why there is that confusion, is because it was the secular, what he was experiencing, versus the sacred. And for us as Black people, from the diaspora, be it the Caribbean, or be it wherever you are in Europe, you need to make sure that you connect to both the secular, and the sacred, in order to fully understand the whole picture. In the UK, we’re just getting the secular, whereas you need to come home to experience the spiritual, the sacred, we’re on indigenous lands and we need to connect in order to get the whole picture, otherwise we will just have a one-sided history and the narrative will continue.

KYC: So beautiful, secular versus the sacred. Thank you for that.

KK: Thank you for the tea party, it’s the best tea party I’ve ever been to!