BLACK LENS: CAROL TULLOCH & TOSIN ADEOSUN

Professor Carol Tulloch and curator and archivist Tosin Adeosun explore the legacy of a Jamaican muse.

InterviewsWe invited Carol Tulloch, writer, curator and Professor of Dress, Diaspora and Transnationalism at the University of the Arts London, and Tosin Adeosun, Curator and Founder of African Style Archive, to delve into the life of a nineteenth century artists’ muse from Jamaica as part of the Future Legacies Black Lens interview series.

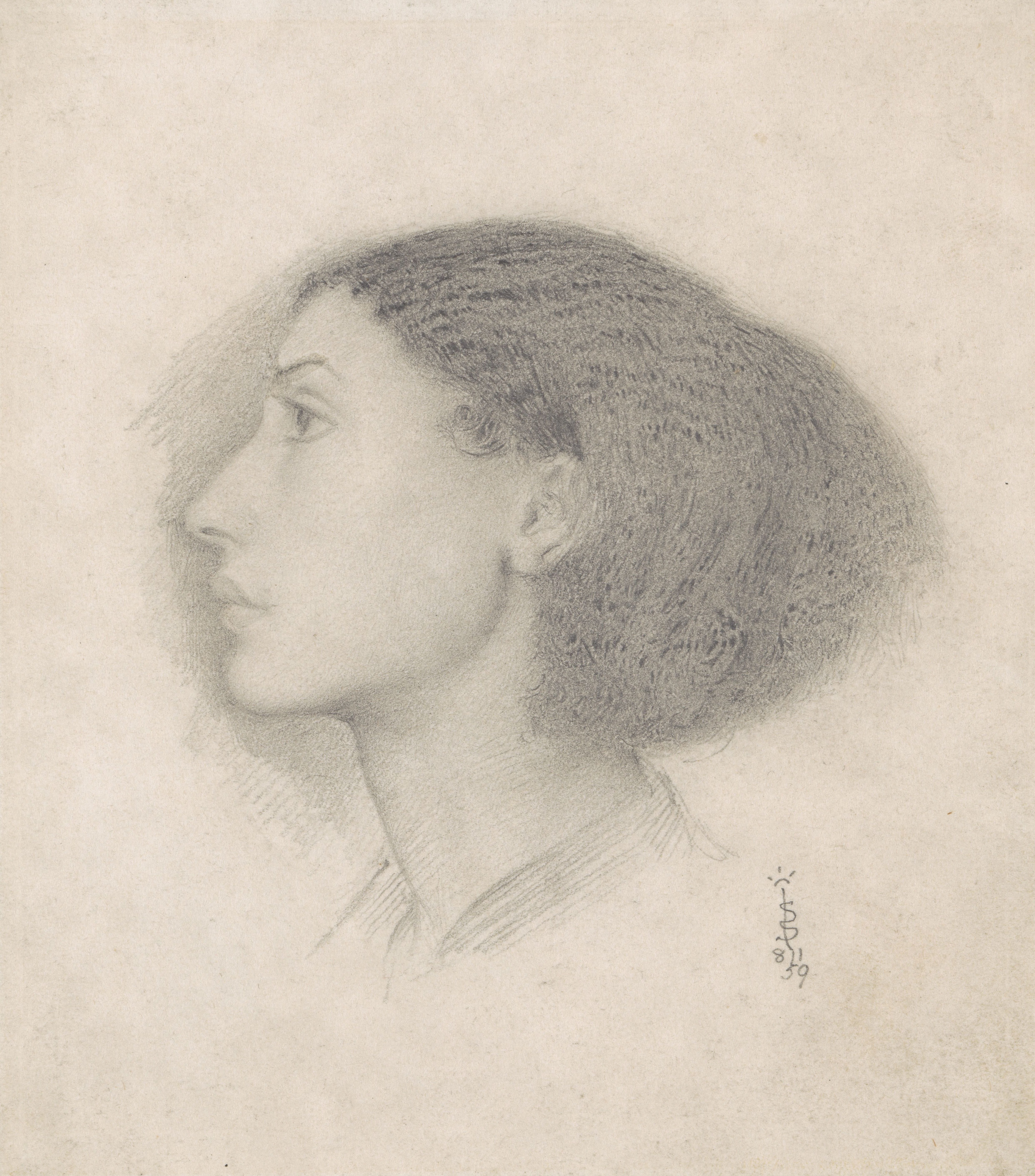

Image: ‘Portrait of Mrs Fanny Eaton.’ Simeon Solomon. 1859. Photo © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.

The conversation

Tosin Adeosun: We have the amazing portraits of Mrs. Fanny Eaton with us, which we are going to talk about today. I thought we could start by looking at the portraits and talking about our first initial reactions to them. What’s your first thought?

Carol Tulloch: Well, what’s lovely [about] these portraits by Simeon Solomon [is] initially I just saw the first 2, the side portrait and Fanny looking down towards the ground, but I’d not seen the full-on face portrait of Fanny, which gives you a range of perspectives and more of in the round, if you like, although we don’t see the back of her head. I think, for me, it’s Fanny Eaton as she was, rather than being styled to represent another cultural group, another group of difference but because you can barely see her clothes, [the] garment she’s wearing is colourless. The focus is on her hair, on her face, [and] of course her beautiful features. If you can come back to this idea of what is beautiful and beauty, prior to us starting this conversation we were both saying, you know, ‘What products was she using? Is her hair natural or did she plait it in some way?’ Which was perfectly legitimate at that time.

What I love [about her profile, are] the waves from the roots from of her hair and then [how] it just fans out and it’s almost like a bob, so that’s much more early 20th century, whereas the third portrait, which is more full frontal, again, you can see the thickness of her hair and that volume, but quite short. It’s quite interesting because in the first [side] portraits you can’t get a sense of her eyes. As you can see, it’s just a side view or her eyelids are closed, but again, in this third study, her eyes are so big, just awake. There’s an engagement with the shape of her lips and the shape of her nose. The thing I thought when I first saw these, [was about] some of the work that I have done, particularly in the 19th century in Jamaica, [where] mainly it’s been market women, domestics, so a lot of them had their hair covered.

It was really rare, except for on Sundays, that [in] photographs of these women, that you could see their hair. I just had a quick look at some of the paintings in, for example, the Black Victorians by Jan Marsh, and the Entangled Pass catalogue for the exhibition of the same name. And there are so many women in there, [where for] their hair, it’s not about the covered head, but it’s about, accentuating or recognising their hair and the quality of their hair. There’s one of a recently found photograph of Mary Seacole and a painting and [for] both documentations, she’s actually got quite long hair, but then the way that the ripples of the roots of her hair [go] out is almost the same here, as Fanny Eaton. It made me think, ‘Okay, how many women depicted at that time, you see their hair?’ And there are lots and I didn’t really thought about that, and the quality of their hair and the thickness of it, and we know that, in that, some of the racist language to do with Black people, whether male or female, their hair would be seen as ‘wool’ and a negative representation of that. In the images that I’ve seen, it’s a real accentuating the beauty of hair that Black women, or mixed heritage, mixed race women, had.

TA: Going back to these drawings, I think what really stood out to me about her hair is how very simple they are. It’s quite timeless in terms of the representation of Fanny Eaton as a model. I’m really drawn to the concept of muses for artists and painters, photographers, film-makers in general. What do you think of Fanny Eaton as a muse?

CT: I completely agree about how Fanny was used as a model. The pre-Raphaelite artists were very drawn to her, in terms of different forms of representations that she could use. In terms of the word ‘muse’ and what we are trying to do today is that ‘muse’ can mean commutate, meditate, reflect, contemplate, ruminate, think over, think about, consider, chew over, deliberate, ponder, which like these studies, be absorbed in thought, be a study, dream, daydream, being in a trance, or reverie. I think it can be a form of reflection. All of those different ways of thinking about what a muse can be and musing or thinking about something fits in well with what we’re trying to do today, but also what these drawings of Fanny Eaton can inspire us to think about [when] talk about past, present, future interconnectedness, if you’re going to look at something.

Sometimes, there is this line where you can connect something that’s happening here with Fanny. At this time, she’d had, I think, two children by this time these studies were done. In discussions, we’ve had before, Tosin, I mentioned there is a stylist and curator called Akeem Smith, who is from Jamaica and brought up in the States, and he did an exhibition called ‘No Gyal Can Test’, which was about women of the dancehall. For me, it’s a curatorial portrait of women of the dancehall and the way that they want to dress and live and how they express themselves, [as] a group that had no voice or not seen as part of Jamaica’s history and then within the strata of Jamaica society was seen as quite low.

Akeem Smith, his art and his grandmother, were very much a part of that group and it was the out crew, and they would make clothing and import wigs and all of that to help women create looks that they wanted to do as part of dancehall. What I’m coming back to is that he’s using these women as a form of muse. He did use those exhibitions as a way to meditate on, but also represent them and show them within an exhibition space and to show a broader understanding of who they are, and then their cultural contributions. In a sense, for me, just seeing those three studies inspired that hat thing of the connection with Jamaica, so there’s a form of a continuous link.

It’s about moments of truth. If a younger generation comes across these images, then there’s that connection and they can see themselves in that past and not in the usual way of enslavement, but in a different context.

Professor Carol Tulloch

TA: There’s another painting [of Mrs. Fanny Eaton] that really sticks to me and it’s the one by Joanna Boyce Wells, [where] she is [represented] quite regal. It’s a different way of seeing her.

CT: Is that the one [where] she’s got hair jewellery as well, which rakes through?

TA: Yes. I just wondered if you had any thoughts to say about that, or initial thoughts?

CT: There’s one, and I can’t remember the name of the painting, it’s quite famous, but her back is to the viewer and she on, Fanny has on, a kaftan, and again, there has been criticism that Fanny has been, although she was Jamaican-British, used to represent different cultural groups that were ‘non-white’. This one, maybe because I’ve got a weakness for kaftans, she has a way [of] just turning and looking to the viewer; you’ve used that term ‘regal’ and it has that quality to it.

TA: I think it’s interesting considering the context of the time as well that Fanny Eaton would have been a sitter for these photographs. In terms of muses, do you have any muses? It could be in the context of fashion, but not in fashion.

CT: If I’m thinking about muses, women that I’ve been drawn to, that I’ve wanted to write about, that I feel that a version of their lives need to be written about. I’ve done one on Billie Holiday. I talk about her life as being a form of collage, a blend of different references, but that then came to make Billie Holiday ‘All of Me’. Another one that I’ve looked at is the market women in Jamaica. I’ve used one specific photograph, which was called ‘A Jamaica Lady’, [where this lady] has this big basket on her head and beautiful apron over her dress that she was going to sell in the market, but that also linked with my family and maternal side, that there were higglers in our family in the early part of the 20th century.

I think, at the heart of it, it’s these individuals artwork or music that they’ve done that’s helped me understand my sense of self in the world and inspired me to do the work that I’d like to do, but also, it’s individuals that have, when you read their autobiographies, how they have negotiated what difference means and the reactions to your difference and how you can, kind of, work through that.

There was something I’d like to read, if that’s okay, so in terms of muses, this is actually Paul Gilroy. I used ‘The Black Atlantic – Modernity and Double Consciousness’ when I was doing my MA dissertation on Jamaica. This is a quote from the book and it says, ‘It is the struggle to have Blacks perceived as agents, as people with cognitive capacities, and even with an intellectual history, attributes denied by modern racism. That is, for me, the primary research for writing this book’. That quote alone inspired me to do my research about Jamaica, late 19th, early 20th century, which is part of my familiar heritage and to get a sense of that history, but also get a sense of who I am.

And then, I was fortunate to interview Paul Gilroy in 1987 and he said, and I quote, ‘the double consciousness of being Black and British, creating ambivalence in Black Britons of either/or-ism. If you’re not one thing, you are an other, when actually you are all different things at once. It’s a question of being able to inhabit them all into a framework without it being a problem.’ It’s this kind of thinking [that] goes straight back to what we’ve got here with Fanny, because we know that her mum was Black, Jamaican, and her dad, we think, is from Europe anyway; and then being brought up in England and the different jobs that she had, you know, seamstress, charwoman, cook, and artist, model and then to the next level, muse.

TA: Also, being a mother, because she had 10 children. That’s a lot of work.

CT: Yes, exactly. She had children by the time these were taken. So, honestly, all of these portraits and then, as you mentioned, the other portraits of Fanny, just made me want to look back and see where we are now or [how] the thinking that has developed. One of the criticisms has been that there have not been enough studies on Fanny Eaton, so that has happened in the 21st century, but something that has been developing.

TA: We were wondering, how did she style her hair, what would she have done, given the time and the lack of tools she would have had.

CT: What about you? Who is your muse?

TA: I have a few across different eras. I love that you said muses could be across genders, across different disciplines and what they represent.

CT: I don’t know why Little Richard just came into my head now as well. That was another one, and I think growing up and seeing, flamboyance, I don’t know, I think being brave in terms of that incredible quiff and then the clothing that he was wearing and definitely makeup, and seeing that, growing up, on TV, that was just mind-boggling. You just saw the possibilities [of] Blackness, there are just so many definitions or what it means to be Black.

TA: The little research that’s been done of Fanny Eaton, she’s always referred to as an overlooked muse and model from that time period. It’s very consistent, seeing her in different paintings and the different ways she’s been portrayed. I wondered if you had any more thoughts in terms of beauty, in regards to Fanny Eaton, or even thinking about the beauty standards?

CT: It’s without doubt that, well, for me, Fanny Eaton is beautiful, but how do you define that and what does that mean when you’re talking about somebody who’s Black or mixed heritage? What does that mean? Just to quote the wonderful Shirley Anne Tate, in her book on Black beauty, ‘Black beauty, as all other beauties, is a matter of doing’. [This] is a bit what you were saying about how your muses, the way that they present themselves, whether they do it themselves or they’re working with stylists, but the doing to create the beauty. What products did Fanny Eaton use? What tools was she using to do her hair? And so, that idea of working with the concept of beauty Fanny Eaton was just triggering, these works were triggering memories of things that I’d seen.

You just saw the possibilities [of] Blackness, there are just so many definitions or what it means to be Black.

Prof. Carol Tulloch

Sometimes, I find it really hard to define what is beautiful or who is beautiful. But, it’s always something, where somebody catches your breath, for me, and makes you look, again. I’ve talked about this briefly somewhere else, but on the Tube, from Walthamstow, having seen Rose Sinclair’s exhibition of Althea McNish and this young woman got on the Tube. The way that Fanny Eaton is represented in a lot of the paintings, the skin tone was about the same, light skin tone, the hair was slicked down, really tight, close to her head into a bun, lots of gold jewellery, there was a lot of Black clothing and there was some red. She had, like, cargo pants, trainers, she had big earphones around her neck. The confidence, not arrogance at all, but there was a confidence.

I’ve actually said it was like she was wearing her bedroom, because I would say she was about 16-17, everything that defined her at that time would be in her private space of her bedroom and that she was wearing this on her body on that day, and I couldn’t stop looking at it, because she looked so, I wouldn’t wear it, it’s not me, too old, but I understood. I got a sense of who she was. I know it’s difficult to place that to an individual, but she just knew who she was. It came across that way. She didn’t look awkward. She just looked incredibly confident and that’s a form of beauty, I think, for me, which is a bit about what you were saying about your muses, because I remember seeing Aretha Franklin on TV, so, this would be the ’60s, in a head wrap and kaftan. I mean, it was just there was a strength there. Well, she’s a good-looking woman anyway, but then it just filled the screen, that power of that beauty. What about you?

TG: I think, like you said, it’s a breathtaking moment. What set the beauty standard that made her the muse in the pre-Raphaelite era?

CT: It’s something that needs more and more research and study, because we know that, at the time, it was the pale white skin that was the beauty standard, but it’s something that needs further study, really. And again, I don’t know, it’s perhaps not very academic, but these three portraits just keep triggering references from the 20th century, but what does that mean? I think if somebody, a child, teenager [was] thinking, ‘What has the 19th century got for me?’ And then they come across these drawings, they go, ‘Okay, I’m connected to the 19th century. This is something I might want to explore more, but it’s not…’. I’m sorry, I’m getting emotional. We belong as part of that history.

TA: It is emotional looking at it from a contemporary angle, but also what it meant in the past. Very important that the past and the present and future come together.

CT: Exactly. It was an exhibition in a book called ‘Beyond Desire’. So, J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, a quote by him in ‘Beyond Desire’, and he says that his photographs of Nigerian hairstyles in the exhibition ‘Beyond Desire’ shift the discussion of the relationship between Black hair and respect into the realm of validation. Within the context of self-respect and self-worth, Ojeikere’s precise documentation of Nigerian hairstyles over 30 years since 1968 are seen by the Nigerian as moments of truth, as he wants them to be memorable traces of them, of the individuals. I have always wanted to record moments of beauty, moments of knowledge, photographs from a visual history in Africa.

We are conscious of appropriating history which has been transmitted for a long time by oral tradition. Ojeikere says, ‘My work as a photographer contributes to the preservation and culture in Nigeria and in Africa in general’. It’s about moments of truth. If a younger generation comes across these images, then there’s that connection and they can see themselves in that past and not in the usual way of enslavement, but in a different context.

It’s about moments of truth. If a younger generation comes across these images, then there’s that connection and they can see themselves in that past and not in the usual way of enslavement, but in a different context.

Prof. Carol Tulloch

Images: Portrait of Mrs Fanny Eaton. Simeon Solomon. 1859. Photo © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.

References:

Jan Marsh, Black Victorians: black people in British art, 1800-1900 (2005)

Akeem Smith, No Gyal Can Test (2020)

Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic – Modernity and Double Consciousness (1993)

Shirley Anne Tate, Black Beauty: Aesthetics, Stylization, Politics (2009)

Rose Sinclair, Althea McNish: Colour is Mine (2022)

D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Ojeikere (2014); Beyond Desire (2006)