ART SCHOOL IS A LUXURY

Is the value of Black cultural production predetermined?

Writer Gwyneth Tambe-Green shares a poetic, poignant and personal essay on entering the world of art, artists and art school.

StoriesI first encountered the notion of a Black Atlantic during my undergraduate degree. For the first time in my academic career, whilst engaging with Black art and cultural production its value was predetermined thus at my liberty to explore. I was enthralled, and at times troubled, by much of the critical theory that contextualised Black art produced in the West during the period of modernity – the dates of which I never managed to pin down, Google being my witness.

I reflect on the interconnectedness of being in the classroom, being outside, locked down and witnessing historical moments. And with all of these passing states, there is space for critical nostalgia, learning via revisiting.

I think back to some moments of personal naivety from this time, and the possibilities and propositions they leave me with now as I find myself studying again, a little less naively I hope…

I felt my face flood with red hot social anxiety.

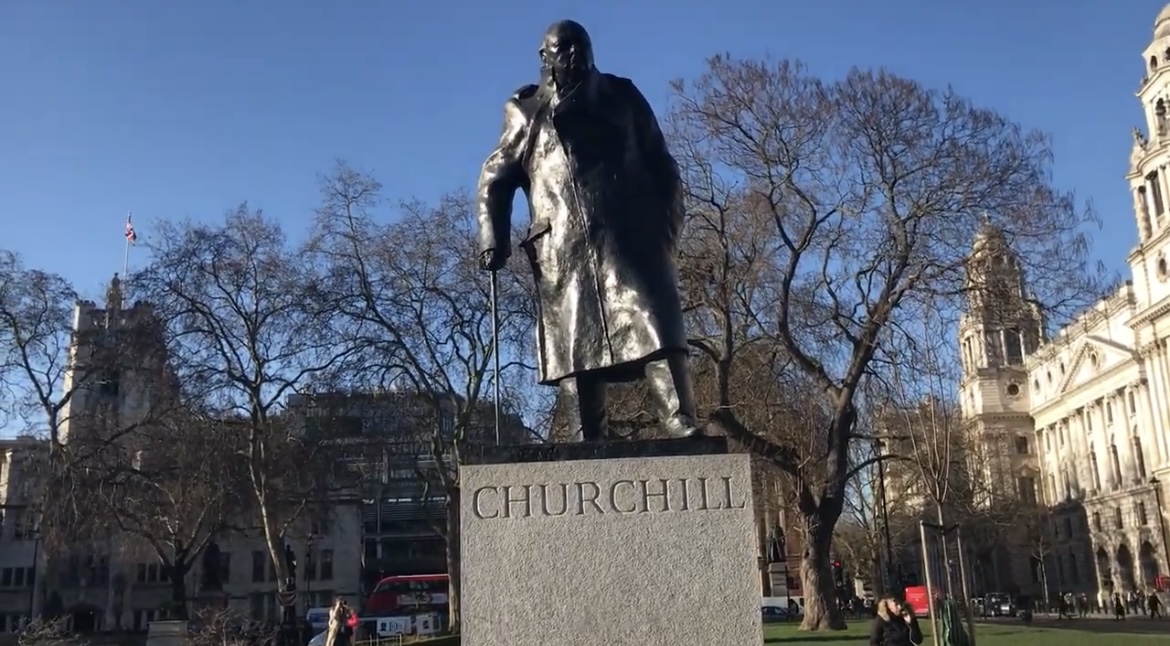

I once walked around London and declared my middle finger at as many statues as I could find to have muddy colonial histories in London. I had just started my first year studying Fine Art and History of Art at Goldsmiths (Class of 2022), and my feathers had been decently tousled by the antagonising pursuit of critical race theory.

Once I had researched as many statues as I could find online, I wrote myself a route and probably set off as early as I could (not before 10am; I was 20).

When I arrived at my first statue, I felt my face flood with red hot social anxiety – I hadn’t thought this through, the performance of it all. Because this is London, it being a weekday bears little on the population of a place like Kensington Gardens. There were a dozen or so there, with a similar idea to me, to document the statue of Queen Victoria as I was, though I doubt highly that anyone intended, also, to flip it off.

I remembered the greater good, and *my Art*. I gulped – still hot, still bothered – and I raised my fist, uncurled my finger, and I hit record. God, my finger looks weird, I didn’t think that through either. I’d broken the seal, so I gave it a few more tries. Thumb in, thumb out, a tight fist, a loose one, knuckles facing me – no that’s stupid – and facing away.

I went on my way, the process getting easier as I ticked off each statue, but still the sense of cool relief swept over me when I’d put my phone away and run from whatever crowd of tourists or finance bros I found myself entangled in.

Six months later is when the Colston statue was toppled.

When I came across Ai Weiwei’s photographs – ‘Study of Perspective Series’, 1995-2003 – of a very similar nature to that of my videos some weeks later, I was crushed.

It was back to the drawing board, and I was fuming. I wasn’t as incensed as I was made by the statues and what they represented, but fuming all the same.

I succumbed to more inspiration, knowing the conversations I was eager to engage in, but with what material still unbeknownst to me.

Six months later is when the Colston statue was toppled.

Four days later I visited Tony Cokes’ show at the Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA), the artist’s first UK solo show titled ‘If UR Reading This It’s 2 Late: Vol 1.’ Exhibited was a series of gleaming text works. I still have blurry photographs of the show which read:

‘Britishness is an integral part of my identity too.’

‘There is a culture of barefaced denial these days.’

‘Those I have spoken to aren’t fooled by you posting a picture of

James Baldwin on the homepage of your website.’

The imprint left on me by these words…

A lot of the show’s broader themes and contexts were lost on me when I viewed it. I wasn’t in the habit of further reading back then as I am now. Nor was I privy to any gallery’s programming beyond the display itself, or intent on meticulously documenting a show’s printed matter.

When I would leave a show those days, I would return quite swiftly to being enthralled by my own 20 year old existence. The remnants of this show, as it exists on my iCloud, is a series of hasty photos, the smudged exterior of my camera lens making me want to rub my eyes in the present.

The imprint left on me by these words, however, was a lasting – pre-existing too, perhaps – sense of how these ideas would come to swell in and out of public relevance. The dates of this show are compelling to me now.

‘those I have spoken to aren’t fooled by you posting a picture of

James Baldwin on the homepage of your website.’

Six months later art institutions – no, every kind of institution – felt eyes burning into the backs of their heads and acted accordingly, for a time.

‘There is a culture of barefaced denial these days.’

Any matter of years, months, or days before or after any kind of moral crisis plaguing the Western conscience. Four years later is right now.

‘Britishness is an integral part of my identity too.’

This same year (2020) my Dad was granted his British citizenship, though he moved here in 1992, when I was -7.

Offeh asked us to take ten minutes to dance as vibrantly as we could.

When the pandemic had subsided a little, likewise had protests, and it felt as though the country was finding itself in a state of collective seasonal depression, artist Harold Offeh visited my undergraduate programme, virtually, proceeding to deliver my favourite seminar from the whole of my undergraduate degree. As Zoom lectures were very much in their infancy, this is a sure testament to the artist.

At the risk of sounding like the rather lazy 21 year old I surely was by then, what has stayed with me most from the seminar was the break in which Offeh asked us to take ten minutes to dance as vibrantly as we could… space permitting. I danced in my kitchen to KCee and Wizkid very privately, optimising the willingness of my energy, and proceeded to occupy the space of cliche: feeling energised, anew and, dare I say, enlightened.

It’s funny, I think, because it was due to my own dismissive attitude towards such collective activities (ones which circle ‘cringe’ which I ironically find all my pleasures in now) that I found myself so surprised at my reaction.

Offeh’s work embodies a range of mediums, including performance, and thinking back to a time where movement in all its forms was so priceless it is true that I still take it for granted.

Likewise, the indisputable privilege of seeing and making art, and having with it transformative interactions.

I’ve flirted enough with the different ways artists choose to engage with institutions and their colonial histories.

I try not to be disappointed now thinking back on the details I might’ve lost when my attention span was shorter. I am left with blurry photographs, the memory of dancing in my kitchen and unfinished work curbed for fear of copying.

Less pessimistically, however, I am also left with a constellation of experiences which define my interactions with art in the present. I don’t have a Tony Cokes back catalogue downloaded in my

head, I have no quotes from Harold Offeh’s seminar and I didn’t make an artwork before Ai Weiwei did, but I’ve instead inherited an exciting inclination towards transformative art and I’ve flirted enough with the different ways artists choose to engage with institutions and their colonial histories.

I have some ideas and the luxury of exploring them, as many of us do and should aim to indulge.

I’ve instead inherited an exciting inclination towards transformative art.

Gwyneth Tambe-Green is a writer. Connect with Gwyneth here.